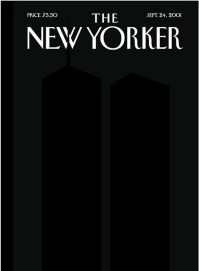

A stark black-on-black image commemorates the victims of 9/11 and communicates multiple elements of the tragedy.

June 19 2011.

The New Yorker, Sept 24 2001

Colour

The grim monochrome colour scheme of this cover is deeply symbolic. The image has only one hue — black — with shapes distinguishable only through saturation (Rose). Combined with the Western cultural symbolism of black as the colour of mourning, the deeply saturated Twin Towers speak to a grief-stricken memory of what was. The block silhouettes of the buildings function almost as an optical illusion; with only a saturation-defined outline to guide the eye and the mind, the Twin Towers could here be fleshed-out buildings, as in Americans’ memories, or voids of mourning, memory-ghosts of both the Towers and all they represented, and of the event of 9/11. I say the event because the destruction of the Twin Towers has become, and really always was, the face of the 9/11 highjackings. It was the only highjacking that reached its final destination and wrought the intended havoc. At first glance, the Towers’ silhouettes appear to be positive space — filled space, tangible objects. But if you look longer, their deep saturation and lack of line draws not only your eyes, but your conscious being, with a semi-mythic sense of approaching a vacuum. Looking at this image for more than a second or two is like staring up-close into a black hole. The less saturated black background, reminiscent of a smoke- and ash-filled NYC, recedes into the peripheries of the image and the mind as the looming memory of the Towers presses forward. The image of the Towers is simultaneously a vacuum and a supernova.

Meaning in the image thus reaches its zenith in paradox; but it doesn’t stop there. The meaning is a paradox that spires between modes, with the black, spire-like lightning rod of the foremost Tower piercing the text, impaling the stark (equally saturated?) white W of “New York.“ The vacuum image reaches forth to create a rift in the text, opening the vacuum of symbolism/feeling/meaning further, inundating the once-sacrosanct mode of text. There is also the religious connotation of the spire: here, in inverted Christian terms, a ghostly black memory reaches towards heaven and redemption. The spire also points to the text, and through the linguistic meaning of the words, to the context: The New Yorker magazine, an American tradition embodying many of the same things as the Twin Towers — wealth, capitalist intellectualism, elitism, free market and monopoly; the New Yorker, the average American citizen devastated by this tragedy; New York itself, the deeply symbolic jewel of America, with its immense wealth, immense poverty, immense variety and charisma. And the W itself subtly brings to mind the (at that time) newly elected president — a particularly complex concept in hindsight.

Note that while Kress writes, on the first page of Multimodality, that “writing names what it would be too difficult to show” [emphasis in original], the linguistic component of this cover is minimal. It adds to meaning, but is a small part of the cumulative meaning generated by the various mode utilized, and dominated by image.

There is a further textual element to the cover that might easily be missed: the price. I here count number as text because of its similar graphic presentation and ways of conveying meaning. At any rate, the presence of a metaphor (Kress) for American currency is, once again, deeply symbolic: the nation is represented through its meaning-claim to its currency, and also through the implied capitalist values of a price tag — which once again links to the symbolism of the Twin Towers, the reason that they, rather than, say, the Metropolitan, were a target.

Font

Please note that I here count font as part of image, as opposed to text: while font is physically/visually bound up with the graphic entity of text, it conveys meaning visually, not linguistically in the way of text-as-a-metaphor-for-speech (Kress). This is evident in the way font functions in this cover: the aforementioned associations of the text with NYC are strengthened by the choice of font the periodical employs, which has encapsulated its symbolism and its context from the beginning — this is the font of the Roaring Twenties, of a time when to some extent, New York symbolically was America. The colour scheme enforces this, but also interacts with the 20’s impending legacy: the Great Depression. Both the Depression and 9/11 remain intrinsically American experiences, horrors that took place on American soil, hitting home, and the image-text ties that occur between them in this cover are deeply meaningful because of this. Pearl Habour, of course, resembles the event of 9/11 much more closely than does the Depression, but the Depression, I think, stands as a metaphor of prolonged national grief. Even the name the Depression embodies suffering.

The block shapes of the Towers chunk information/meaning. The boundaries between Tower and background are hazy at first, due to the monochrome, but become clearer the longer you look, until the Towers push the background into temporary oblivion, with the many meanings of 9/11 imbuing the image and the mind, as discussed above. [image/ mind gestalt] This is not to suggest that the use of the background space does not carry meaning. Layout and space add greatly to the meaning of this image. The very plainness of the surrounding space gives the image of the Towers a medium in which to mean. It also suggests the existence of NYC around the Towers, subtly connecting the entire city to the tragedy focalized by the image of the Towers.

Line is also important to the meaning of this image. The sharp angles and shapes of the cover echo the stark, saturated, monochrome colour scheme; vectors also add dynamism to the image. The top corners of the Towers jut out at the viewer, helping to create the vacuum effect discussed above; the sharp vectors also function as metaphors for the cutting grief born of 9/11.

Bibliography

Kress, Gunther. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. Axon: Routledge 2010. Ch 1, 4.

Rose, Gillian. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials, 2nd ed. London: Sage 2007. Ch 1, 3.

July 7 2011.

I was just rereading chapter 5 of Rose’s Visual Methodologies and there is something in particular I want to respond to. On page 102 of my edition, Rose states the following:

Semiologists would argue that adverts do indeed deal with serious issues: they engage with some of the most important issues, indeed, with questions of social difference and social hierarchy. But part of their power is precisely that they are not seen like that. … This explains much of the controversy surrounding the advertising campaigns produced in the early 1990s by the clothing company Benetton…. Their ads showing a man dying from AIDS-related illness, or a bombed car in an Italian street, caused outrage because these images challenged the reception regime of advertising. They were clearly asking their viewers to engage with “big” issues — death, violence — and this violated the regime’s rules that adverts do not do that. The ensuing efforts by other advertising agencies, by magazines and the rest of the media…to re-establish the reception regime by branding these images immoral or obscene reasserted once more the apparent harmlessness of noncontroversial advertising.

Rose does not include a copy of the image in her analysis. See http://theinspirationroom.com/daily/2007/benetton-pieta-in-aids-campaign/

While I appreciate the point that Rose makes, I feel that she asks her readers to jump to a conclusion when she claims that Benetton’s campaign’s controversy is due (only) to the violation of advertising’s reception

regime. There are situations where such images could be appropriate means of advertising — if Benetton were donating money to AIDS relief efforts, the image of the dying man might not have been construed as offensive. Similarly, I have never heard anyone say that the poignant images used in adverts for World Vision are offensive. However, if there is no morally sanctioned connection between the disturbing image and the product being sold, then it would seem that the image (and by extension, the real-world event or person) is being exploited to line the pockets of (in the above case) Benetton’s CEO. Rose doesn’t specify how the images fit into Benetton’s adverts, so it’s hard to judge whether the media’s outrage (and perhaps viewers’ as well? But again, Rose doesn’t specify) is due to the violation of the reception regime, or to the moral issues I’ve raised. If these images were used in an appropriate setting (such as fundraising for AIDS relief or for the victims of the bomb), then I might attribute media outrage to the violation of a reception regime. If, however, they were included in the ad merely to get the viewers’ attention, I would be offended too. Suffering is, one might even say, sacred: and to use an image of suffering — even more viscerally, a photograph, a primary documentary source — purely for financial gain is to exploit it, at least within the values projected by the society I live in. The metaphor of prostitution feels apt here; the feelings of victimization and violation that the idea of prostitution evokes in me as woman tap in to the extreme suffering I, as a viewer, perceive in the image of a man dying from AIDS or of the aftermath of a terrorist bomb.

From this perspective, I’d like to analyze the New Yorker cover I talk about in my first post. I find it unlikely that American audiences were offended by this image. Magazine covers are adverts, really — they’re adverts for that issue of the magazine; they’re supposed to make you want to buy it. However, this issue of the magazine centres on the tragedy of 9/11 and, presumably, on recognizing and trying to come to terms with the suffering that resulted from it. If a post-9/11 magazine featured a picture of the Twin Towers just to sell its articles on sex or knitting, I think people would probably be pretty upset (maybe less so as regards knitting, but still). Doing this would reduce this traumatic moment in the life of a country and culture to a fraction of its meaning. It would bring it down to the level of selling things, of money (somewhat ironically, in the case of the Twin Towers, it must be admitted) from the level of the heartbreaking and the sacred. It’s hard for me to think of a Canadian parallel, but imagine if they used a picture of Terry Fox to sell popcicles. So, the cover under discussion forms a potential antithesis to the Benetton adverts: a big issue, a very serious, a sacred, image of suffering upholds the norms — or the reception regime, if you will — of advertising because of the context in which the image is displayed. By the context, I here mean the magazine, the articles which the image symbolizes and the reasons for using the image to sell the magazine.

From this perspective, I’d like to analyze the New Yorker cover I talk about in my first post. I find it unlikely that American audiences were offended by this image. Magazine covers are adverts, really — they’re adverts for that issue of the magazine; they’re supposed to make you want to buy it. However, this issue of the magazine centres on the tragedy of 9/11 and, presumably, on recognizing and trying to come to terms with the suffering that resulted from it. If a post-9/11 magazine featured a picture of the Twin Towers just to sell its articles on sex or knitting, I think people would probably be pretty upset (maybe less so as regards knitting, but still). Doing this would reduce this traumatic moment in the life of a country and culture to a fraction of its meaning. It would bring it down to the level of selling things, of money (somewhat ironically, in the case of the Twin Towers, it must be admitted) from the level of the heartbreaking and the sacred. It’s hard for me to think of a Canadian parallel, but imagine if they used a picture of Terry Fox to sell popcicles. So, the cover under discussion forms a potential antithesis to the Benetton adverts: a big issue, a very serious, a sacred, image of suffering upholds the norms — or the reception regime, if you will — of advertising because of the context in which the image is displayed. By the context, I here mean the magazine, the articles which the image symbolizes and the reasons for using the image to sell the magazine.

A minute ago I looked up the photographs Rose mentions, and it turns out that for the photograph of the dying man, Benetton did donate money to an AIDS foundation. University of London webpage The Inspiration Room (http://theinspirationroom.com/daily/2007/benetton-pieta-in-aids-campaign/) cites other issues viewers had with Benetton’s use of the image. Rose, however, does not, and this omission leaves a big gap in her argument. Even with the knowledge that Benetton did donate money to AIDS relief and that it was other significant issues that caused controversy, I am still not convinced that this controversy boils down to reception regimes. Besides being annoyed as someone studying rhetoric and logic, I am, much more significantly, angry that issues like sexual equality and fear/acceptance of victims of AIDS have been boiled down in Rose’s book to a discussion of “reception regimes” without even an honorary mention.

A minute ago I looked up the photographs Rose mentions, and it turns out that for the photograph of the dying man, Benetton did donate money to an AIDS foundation. University of London webpage The Inspiration Room (http://theinspirationroom.com/daily/2007/benetton-pieta-in-aids-campaign/) cites other issues viewers had with Benetton’s use of the image. Rose, however, does not, and this omission leaves a big gap in her argument. Even with the knowledge that Benetton did donate money to AIDS relief and that it was other significant issues that caused controversy, I am still not convinced that this controversy boils down to reception regimes. Besides being annoyed as someone studying rhetoric and logic, I am, much more significantly, angry that issues like sexual equality and fear/acceptance of victims of AIDS have been boiled down in Rose’s book to a discussion of “reception regimes” without even an honorary mention.

July 14 2011: update on July 7 post.

So, I’ve been reading through chapter 7 of Rose’s Visual Methodologies and I have some more ideas. Mostly I’m still annoyed as a scholar and I want to apply Rose’s own theories in my critique of her above, but I will also try to work them into my discussion of the New Yorker cover, if I can do so in a way that fits in this essay. Or maybe I’ll just have to start a new post…hmm… I’ve also been reading through Kress’ Multimodality; chapter 6 seemed a bit garbled to me (I seem to be on an acidic criticism streak!). Kress’ work, at least in this text, tends to have very densely interwoven ideas, but I found up until this point that his work clicked with me. I felt that I understood what he was saying. It’s possible that I’m just not used to working with the ideas he’s presenting in this chapter though. I need to revisit it and see if I can trace his line of reasoning more clearly. Next up: 8 and 9 of Rose, 8 9 10 of Kress.

July 19 2011: more on July 7 post

Right, so I’ve got a couple of things to say about Rose’s section in chapter 5 of her book (the topic of my July 7 posting).

Rose devotes two chapters (7 and 8 ) of Visual Methodologies to a discussion of discourse, rooted in Foucauldian theories of discourse. A central point, or perhaps the central point, of Rose’s overview of the subject and, Rose claims, of Foucault’s work and of discourse analysis, is that discourses are self-perpetuating power structures. In a sense, they’re cons (as in con-men). Discourses claim truth through the assumption that they are right: I say it is so (therefore it is so). What makes this strategy so difficult to pinpoint, particularly from within the discourse, is that the therefore it is so is often implicit in such truth claims. An argument you can’t see is very difficult to objectively analyze and to argue against, should you wish to do so.

Most of the time, Rose offers what look to me like reasonably objective renderings of rhetorical theories (too many r’s!), writing as an outsider (and so not an identifiable partisan). However, in the passage in chapter 5 that I got so worked up over (above), she puts in her own two cents. The thing is, she’s not that objective about it. Kress goes out of his way, at least at certain points in his book, to make it clear what he’s saying is his opinion (see the discussion of reach in chapter 1, pp. 8–11). But here, Rose doesn’t do that. It’s funny, because she carefully situates other theorists in their discourse (though not necessarily using the terms of discourse theory), making it clear that they’re bound and motivated by specific assumptions. She doesn’t do this when propounding her own ideas. Rose throws reception regimes at the reader without offering  a disclaimer, making a truth claim through assumption — the great evil of discourse. I might bend one of Kress’ terms and suggest that Rose is making an (e)valuation; when she partakes in what I might call primary rhetorical analysis — not analysis of another theorist, but direct, truth-claiming use of theories to analyze an artefact — she falls into the truth-claim trap. Thing is, like I said before, she doesn’t include a disclaimer, a this-is-just-my-theory statement. I feel like this fits in with the bit above where I say that Rose doesn’t provide the reader with a context for the images of the Benetton ads — again, she’s making a truth-claim through assumption.

a disclaimer, making a truth claim through assumption — the great evil of discourse. I might bend one of Kress’ terms and suggest that Rose is making an (e)valuation; when she partakes in what I might call primary rhetorical analysis — not analysis of another theorist, but direct, truth-claiming use of theories to analyze an artefact — she falls into the truth-claim trap. Thing is, like I said before, she doesn’t include a disclaimer, a this-is-just-my-theory statement. I feel like this fits in with the bit above where I say that Rose doesn’t provide the reader with a context for the images of the Benetton ads — again, she’s making a truth-claim through assumption.

To move on to Kress, I found his ideas in chapters 9 and 10 of Multimodality very compelling. I’m not sure how truthfully they can be applied to the 9/11 New Yorker cover though. This cover does engage with a lot of the things Kress talks about — particularly the emphasis on visual output in his analysis of mobile phones in chapter 10. However, I think the emphasis on visual output in the New Yorker cover speaks to mourning as opposed to current modalities. The image’s sparseness in hue, shape, number of objects immediately and literally present (see the discussion of colour and layout in my June 19 post) is a sign of respect, just like black monochrome is a sign of respectful mourning in this context. (Ok, to really practise what I preach, I should put something like “could be construed as a sign of respect” so as to avoid making a truth-claim through assumption.) The radically minimized amount of text (price, magazine title, date) could also be read as a mark of respect, and I think probably would be included as such in most magazines commemorating a tragedy. New Yorker covers always, as far as I can see, include a single image with minimal text, so the communication of grief and respect coming from this corporate entity is principally carried by other modes. And yet in combination with said other modes, the absence of text still feels meaningful to me.

Anyway, moving on — bearing in mind the opinions I’ve just expressed, it’s possible that the emphasis on the visual is a mix of grief/respect and of recent changes in the ways we communicate — it would be interesting to analyze the New Yorker cover commemorating Pearl Harbor, but I unfortunately couldn’t find it during my online search just now. If I did manage to find it, I’d compare the modes used and see whether there were differences that could (potentially) be explained by changes in emphasized modes (i.e. visual output over textual/kinaesthetic input; Kress 186).

Bibliography

Kress, Gunther. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. Axon: Routledge 2010. Ch 9, 10.

Rose, Gillian. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials, 2nd ed. London: Sage 2007. Ch 5, 7, 8.

Just an interesting thing I thought of the other day: the can for my shaving cream says “Skintimate” for the English brand name and “Delicaderme” for the French brand name. I was wondering whether creating a new word from two words mushed together works in French the way it does in English, and then I started thinking about how it works in English. Seems to me that when you create a word for something, and give it its own name in Kress’ sense (ch 6), it gives that thing higher ontological status; and that when you make it a name, in the traditional sense (as opposed to Kress’ sense) — a proper noun, especially — it achieves very high ontological status indeed. Which I suppose is one of the ideas behind branding.

August 1 2011.

Transduction: In my first post (June 19), I wrote the following:

“Meaning in the image thus reaches its zenith in paradox; but it doesn’t stop there. The meaning is a paradox that spires between modes [emphasis added], with the black, spire-like lightning rod of the foremost Tower piercing the text, impaling the stark (equally saturated?) white W of `New York.` The vacuum image reaches forth to create a rift in the text, opening the vacuum of symbolism/feeling/meaning further, inundating the once-sacrosanct mode of text [emphasis added].”

A possible transduction of Kress’ proposed terms “translation,” “transduction,” and “transformation.”

This seems to be less straightforward than the motivated, direct mode-to-mode translation that Kress lays out in Multimodality — although the “straightforward” transduction Kress lays out is, of course, not really straightforward (Kress 124-5). The meaning of the image is not translated into words, as one might expect of Kress’ transduction; rather, the way the image interacts with the text-as-a-physical-entity is what carries meaning from the image to the text, and over to the linguistic meaning of the text (everything implied by the words “The New Yorker,” as discussed in the June 19 post). This transduction, if we may call it such, is not directly translated from one mode to the other: meaning travels through the interacting affordances of the modes of image and text, rather than taking the shortcut (or scenic route?) of the theorist’s mind and going straight from “the crowded centre” (Kress 108) of the image to that of the text.

Design: As Kress and many others observe, times have once again changed (or are continually changing, I think). Kress stresses this point during his discussion of design: it is now agency/interest, not prescription, that drive and shape communication. “Formerly stable resources [are] unreliable” (Kress 132); but “in the neo-liberal capitalist market…the resumption of agency by individuals — urged by the state and forced by the market — means that the shaping of meaning[,] and of identity, becomes a matter of individual design” (Kress 134). Might be missing something, but the New Yorker cover under discussion here actually seems very conservative to me — it plays within the rules. This makes it feel “appropriate” and “respectful” to me; something loud and flashy and flamboyantly individualist would seem to be placing the ontological importance of the creator(s) of the semiotic entity above the ontological status (rights and dues) of the dead. This image-based cover, with little text (quasi-sound) — sort-of-silence aimed as a traditional mark of respect; few colours and only those traditionally, conventionally associated with mourning; a general sparseness (of text/language, colour, number and complexity of shapes); engages, or claims to engage, closely with the specific, appropriate marks of respect shown the dead (and also the powerful — is this why big businessmen are usually shown in black suits in the movies?) of the specific (supposedly unfragmented and uncontested) cultural (social, ethnic, temporal, georaphical) context to which it is (attempting to) communicate. This, I think, leads into my next section….

Discourse: So, to refer to my June 19 post again:

“There is also the religious connotation of the spire: here, in inverted Christian terms, a ghostly black memory reaches towards heaven and redemption. The spire also points to the text, and through the linguistic meaning of the words, to the context: The New Yorker magazine, an American tradition embodying many of the same things as the Twin Towers — wealth, capitalist intellectualism, elitism, free market and monopoly; the New Yorker, the average American citizen devastated by this tragedy; New York itself, the deeply symbolic jewel of America, with its immense wealth, immense poverty, immense variety and charisma.”

My inclination would be to refer to the ideology/ies present in the image as described above as “Americanism”; however, as a good postmodernist, I feel obliged to talk about multiple Americanisms, each rooted in differing cultural, religious, ethnic, gender, class (and more) experiences, different geographical locations (Rose 218), and different times. Clearly — overtly — present in the cover as I analyze it are (a particular branch/es of) Christian discourse in the metaphorical spire, and (particular branch/es of) capitalist discourse in the martyred Twin Towers. American nationalist discourse is present through this interaction between (one form of) American Christianity and of (the) American- (state/market’s) style capitalism. I suggest this as context; but additionally, in Kress’ words, discourse provides “‘content'” as well as “a social-conceptual location” (114). When interpreted within the ideological frames of “American” Christian discourse, “American” capitalist discourse, and American nationalist discourse, the Sept. 2001 cover is imbued with a very specific content: it embodies a nation’s (or certainly part of the population’s, to be properly post-modernist) grief, anger, fear over a devastating attack on a very material pillar of its socio-cultral-economic way of life, one of its central symbols — one of its key metaphors, in Kress’ terms.

Audience Studies: So I got my roommate Dan to be my audience (and unconventionally analyzed a still image, not a tv program)….

What does this image mean to you? Dan identified the meaning-content of the cover as being 9/11. He interpreted the cover as expressing “how 9/11 affected many people in New York, so that’s why it’s called the New Yorker,” citing the World Trade Centre Towers as a signifier of the event. 9/11, says Dan, popped an illusory “bubble” of safety; “suddenly people know the world has bad people, terrorists. People’s perspective is changed with the loss of their family and everything else.” The semiotic ensemble (of modes in this entity) is “gloomy; the black and grey mean something that is past, or just recently happened.” The colours are “dull” and “serious,” communicating (in this context) a “tragedy.”

Do you agree with what it is saying? Dan touches on authorial intent, or Kress’ agency: “this is the tone the writer or editor of the article wants to set.”

It’s a magazine cover; how does this affect what it means? Would it mean something different if it were, say, a poster? The price tag is “a distraction” that “diverts from the main issue”; in fact, it “spoils it.”

Dan seems, to me, to have a preferred reading of the cover — he agrees with what he perceives it to be communicating (which is pretty much the same as what I perceive it to be communicating). However, this semiotic entity has another context (maybe more) besides that of (the “American” perspective on) 9/11: it’s still a magazine, a documentary entity (as the date shows) and a corporate one (as the price tag shows). As a magazine cover (see my July 19 post), it is created in part to sell the magazine — but this (ontologically lower?) function “spoils” the artefact’s (morally purer?) role as a memorial. With this in mind, I’d say that Dan has an oppositional reading of the cover as an advertisement, but a preferred reading of it as a memorial. Does this add up to an overall negotiated reading? That doesn’t seem quite right to me…I would analyze these two functions of the cover as being different, although obviously connected through their coexistence in the artefact. It seems to me that Dan may be going in that direction too, although it’s hard to tell from our very brief interview. His use of the word “spoil,” in particular, which significantly didn’t occur until the end of our interview, seems to me to suggest an ontological hierarchy (in Dan’s reading) with reverence for the tragedy and the dead at the top.

Anthropological Approach: above, I examined (my arm-chair understanding of) the socio-cultural context of this artefact. I emphasized both the projected unified “American” identity and the fragmentation, multiplicity, and hybridity of America and, thus, of American identities. The cover presents one semiotic entity, I would argue (although I’m not sure whether the use of different modes would automatically constitute a corresponding number of semiotic entities in a “Kressian” sense). The foremost socio-cultural references/discourses that strike me, as I said above, are 1) the American Christian context, 2) the American capitalist context, and 3) the American nationalist context. (I’ve taken off the quotation marks because it’s struck me that any reference to any one American Christian/capitalist/nationalist context is necessarily a reference to any and all others, simply by association — and this holds true whether the connection is (intended to be) overt, implicit, or unacknowledged.) I suppose anthropology plays into this in other ways too: the existence and role of a magazine (documentary resource and social and corporate entity), the technological resources that reshape the affordances of modes (for example, what/how you put something in an image — perfectly straight lines, pixelation, mass production), the geo-temporal affordances of location (in terms of production, distribution, the transmission of knowledge pre- and post-publication); and more. But oh my goodness me it’s 10 and I have to get up for work tomorrow, so I’m signing off.

Bibliography

Kress, Gunther. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. Axon: Routledge 2010. Ch 5, 6, 7.

Rose, Gillian. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials, 2nd ed. London: Sage 2007. Ch 9, 10.

Just wish to say your article is as surprising. The clearness for your put up is just cool and i can think you are knowledgeable in this subject. Well along with your permission allow me to clutch your RSS feed to keep up to date with drawing close post. Thank you a million and please carry on the rewarding work.

LikeLike

Hey Kristina! Sorry I took so long to respond :S I haven’t been on the interenet much lately because I’ve been putting in so many hours at work, and I also needed to look up what an RRS feed is! I need to double check with someone who knows about copyright and stuff like that, but I don’t foresee any problems with subscribing through an RRS feed 🙂 I really appreciate your interest and your comment!

LikeLike

Hello, i believe that i noticed you visited my web site so i got here to “go back the prefer”.I’m trying to in finding things to improve my website!I suppose its ok to make use of some of your ideas!!

LikeLike

Hi Carleen, thanks for commenting!! Sorry I took so long to reply – I’ve been working a lot lately and haven’t been on the internet much. What sort of ideas are you interested in using on your website? If it’s the graphics that you’re interested in, that’s actually automatically generated by WordPress. If you’re interested in using my ideas about social semiotics or other stuff I write about, I just ask that you cite me according to academic standards 🙂 Thanks again for reading my blog and for your supportive comments!

LikeLike

I like to disseminate knowledge that I have accrued with the yr to assist improve group efficiency.

LikeLike

Hi there, thanks for commenting! Do you mean that you want to disseminate my post? Maybe I don’t properly understand what you mean.

LikeLike

Hiya! I just wish to give an enormous thumbs up for the great data you may

have here on this post. I will be coming again to your weblog for more soon.

LikeLike

Hi, I do think this is a great web site. I stumbledupon it 😉 I am going to return once again since I saved as a favorite it.

Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and continue to

help other people.

LikeLike

Hello! I just wish to offer you a big thumbs up

for your great info you have got here on this post. I will be coming back to

your web site for more soon.

LikeLike

Pingback: ショルダーバッグ